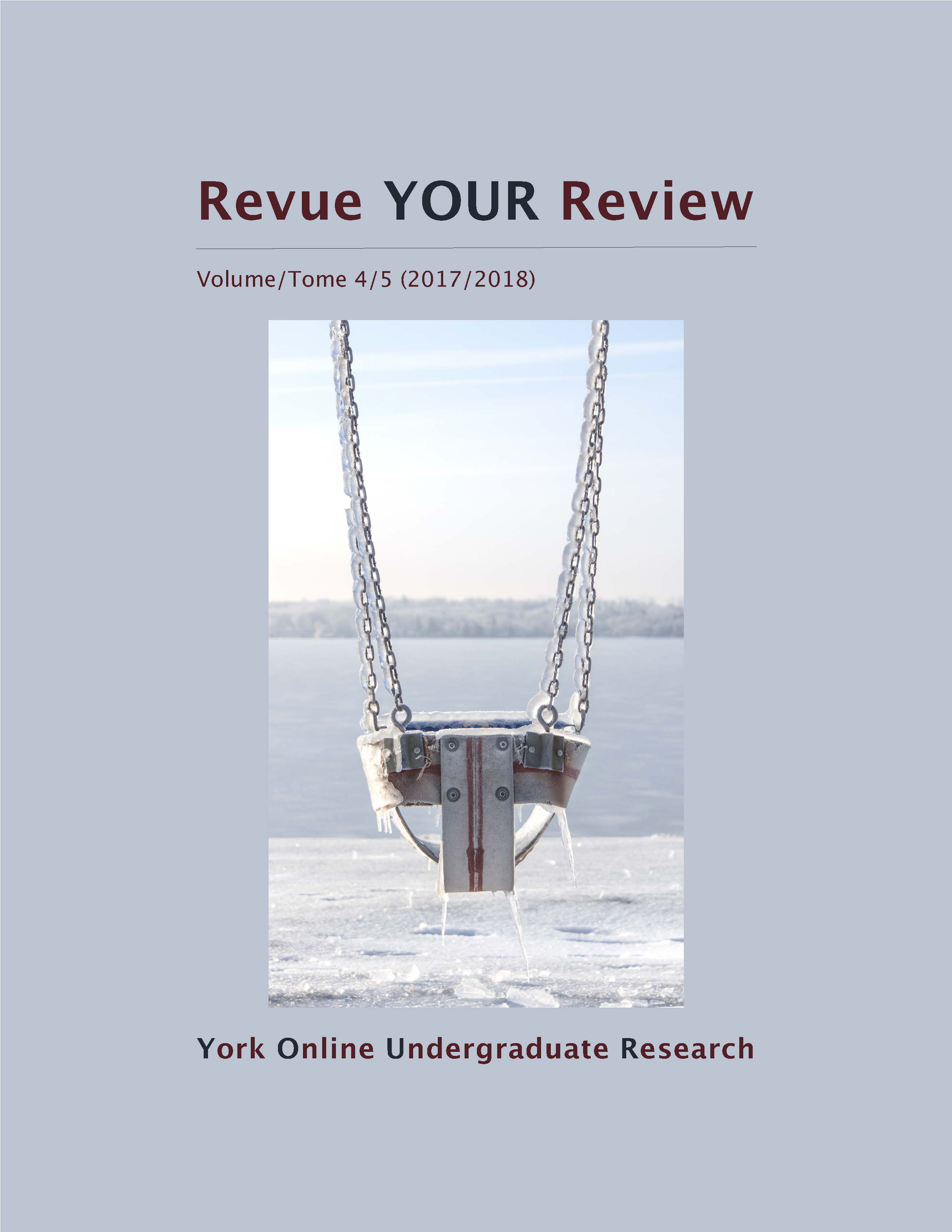

Editorial. Frozen Chains of Childhood (2017)

Abstract

Frozen Chains of Childhood (2017)

Print on photopaper, 25”x15”

***

The photograph Frozen Chains of Childhood was captured in 2017 after a January ice storm in Barrie, Ontario, Canada. The piece is a reflection on the residential school systems, in operation in Canada from 1831 to 1996. Enforced by the Canadian government and supported by the Catholic church, residential schools were designed to “kill the Indian in the child” by forcibly removing Indigenous children from their communities and placing them in these so-called schools. In 1920, Deputy Superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs Duncan Campbell Scott details the schools’ intent: “Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department.”

According to the charitable organization Reconciliation Canada, there were over 130 residential schools in operation across the country. However, this number excludes day schools and other boarding schools that have not officially been categorized as residential schools, even though they too operated under a similar mission. It has been estimated that 150,000 Indigenous children were forced to attend residential schools and over 90% suffered severe physical, mental, emotional, and sexual abuse, resulting in intergenerational traumas still felt by many Indigenous families today.

Many children experienced malnutrition, diseases such as tuberculosis, and forced sterilization, and many were used in experimental trials without parental consent. Research shows that malnutrition during childhood can cause intergenerational health complications, as seen in the higher rates of diabetes in Indigenous communities. Likewise, studies demonstrate that childhood abuse and trauma have a lasting impact on a person and can extend through multiple generations.

Like the swing in the cover photograph, many Indigenous children felt isolated, frozen, neglected, and immobile at these schools. They were trapped in these institutions and while some, like Chanie Wenjack, tried to run away, others could not. There was a 40–60% mortality rate of children in residential schools (Reconciliation Canada). As I write this editorial, over ten thousand children in unmarked graves at residential school sites across North America have been found, bodies recovered, and spirits beginning to return home. For years, Survivors have been speaking about these graves, but it is only now that the truth is being confronted and shared widely for Canadians to reflect upon. With this truth comes pain, but also healing. As the bodies of these children are found and returned home, the truth behind the residential school system becomes widely known and the frozen chains of childhood begin to melt.

It is important to note that this truth is not simply a dark chapter in Canadian history, but rather an ongoing chapter. Indigenous children are still being taken away from their families—first into residential schools, then through the Sixties Scoop, and now through the foster care system. Census Canada data (2016) shows that over 52% of children in foster care nationwide are Indigenous, even though Indigenous children make up only 7.7% of the country’s child population under the age of 15. Today, there are more Indigenous children in care than at the height of residential school system. Although the last federally run residential school closed in 1996, the systems that created them are alive and well.

The Chief Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Senator Murray Sinclair, once said, “education has gotten us into this mess, and education will get us out” (Senate of Canada Debates, 2017). It is through education that I have begun to melt the chains of my community and unpack my own identity as a Cree-Métis woman who came through the public education system without ever learning about residential schools. It was not until the third year of my undergraduate degree, when I chose to enroll in an Indigenous Health and Healing course with Professor Jon Johnson (York University, Toronto), that this truth was shared with me. Until then, I did not understand why members of my family had kept our Indigenous identity a secret and felt compelled to pass as white, for the safety of themselves and their children. Learning the truth has forever changed my life. It has put me on a path of learning, unlearning, and relearning so that I can reclaim my culture and pass it on to future generations. Although it was not safe for my ancestors to be Indigenous, I hope that my future children can grow up in a world where it is not only safe, but celebrated.

—Marissa Magneson is a Cree-Métis artist, photographer, educator, and workshop facilitator. She is currently a doctoral student in the Faculty of Education at York University.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Authors contributing to Revue YOUR Review agree to release their articles under one of three Creative Commons licenses: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International; or Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International. All editorial content, posters, and abstracts on this site are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International. For further information about each license, see:

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/

In all cases, authors retain copyright of their work and grant the e-journal right of first publication. Authors are able to enter into other contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the e-journal's published version of the article (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book or in another journal), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this e-journal.